Curing Throttle Hesitation in Carbureted Lamborghinis

Copyright 2001 - Joe Martz

Disclaimer: The information contained in this article is true and correct to the best knowledge of the author. Changing or tampering with any emissions-control device on a road-legal U.S. automobile is a violation of federal regulations. The author and Lamborghini Web disclaim all liability incurred in connection with the use of this information.

Many of the early, carbureted Lamborghini's, especially the V12's, have a pronounced hesitation when the throttle is quickly applied. In extreme cases, it's possible to stall the engine by a quick and sudden stab on the accelerator. The cause of this hesitation - and the solution - lies in the accelerator pump circuit on the side-draft Weber carburetor.

The Weber carburetor is a master of engineering. Its function is deceptively simple to describe and maddeningly complex to implement: simply put, a carburetor must attempt to maintain the proper ratio of fuel to air under a variety of operating conditions. The complexity arises from the widely differing operating conditions that an engine will encounter. (For a good description of these conditions and the elegant solutions that Weber has engineering to accommodate them, I recommend the books listed at the conclusion of this article.)

For the purposes of understanding and curing throttle hesitation, a description of the accelerator pump is useful. Under normal, steady conditions, the engine draws fuel through the carburetor using vacuum supplied by the pumping action of the pistons and valves. This vacuum draws fuel through the idle and main circuits of the carburetor. In addition, the main circuit of the carburetor relies on the "venturi effect" to draw fuel. The magnitude of this effect is proportional to the quantity of air which flows through the carburetor. When the accelerator is applied, the throttle plate in the carburetor opens, allowing more air to enter the engine. Immediately, the engine sees this increase in air. However, the increased fuel flow necessary to balance the increased air isn't immediately available (because the venturi has yet to be established). Thus, a lag exists between air and fuel flow during acceleration. If left uncorrected, this momentary lag would cause a drastic leaning of the mixture and in certain conditions, enough leaning to stall the engine.

Fear not, since the trusty Weber engineers anticipated this problem and designed a special circuit and features to compensate. A small, independent pump is present in the carburetor. It holds a reserve of fuel which is injected through an auxiliary jet directly into the carburetor throat when the throttle is opened. The quantity of fuel injected varies depending upon the amount and rate at which the throttle opens. One feature of Weber carburetors is there immense adjustability. The accelerator pump is no exception: nearly all aspects of accelerator pump operation are adjustable.

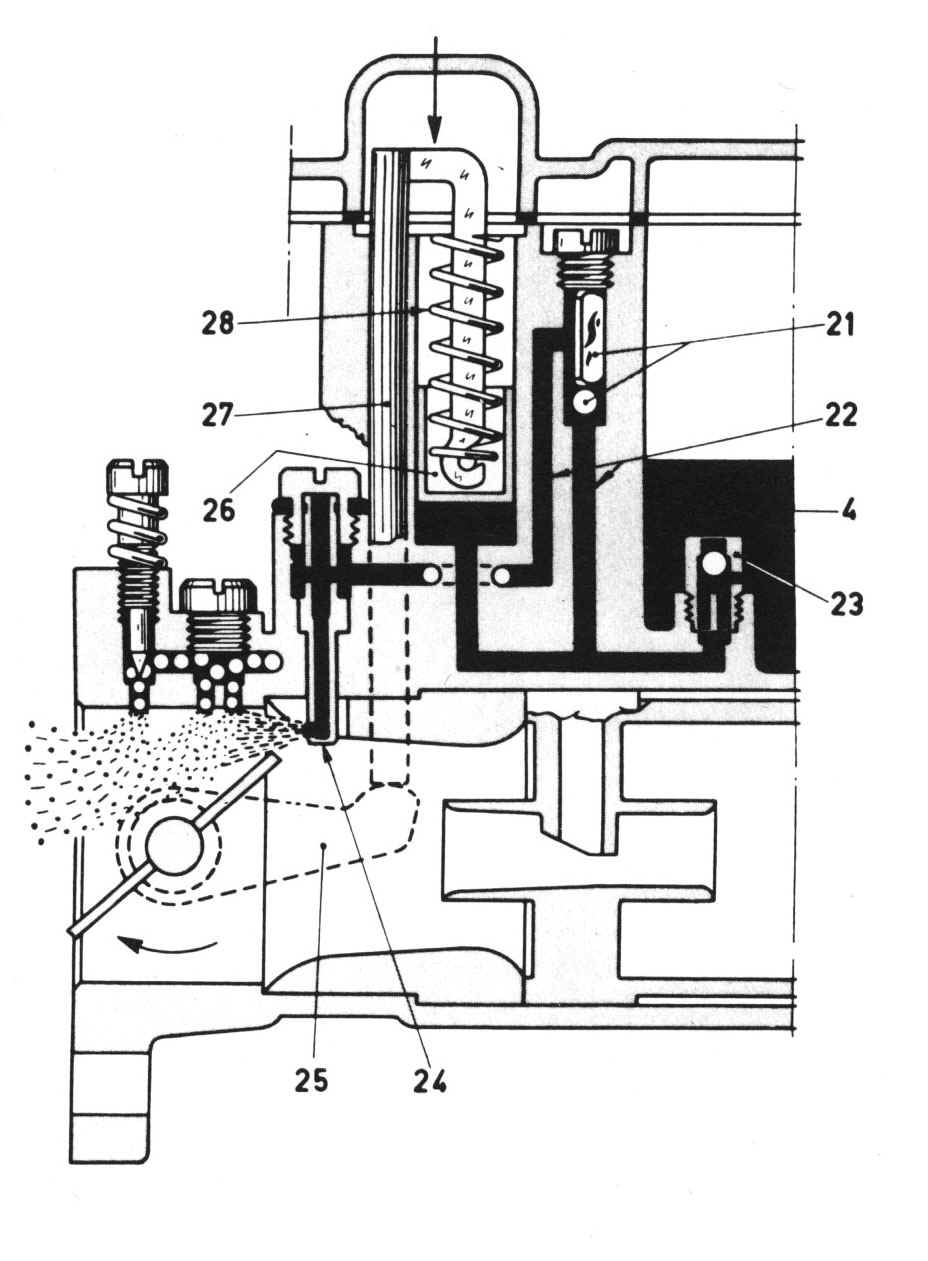

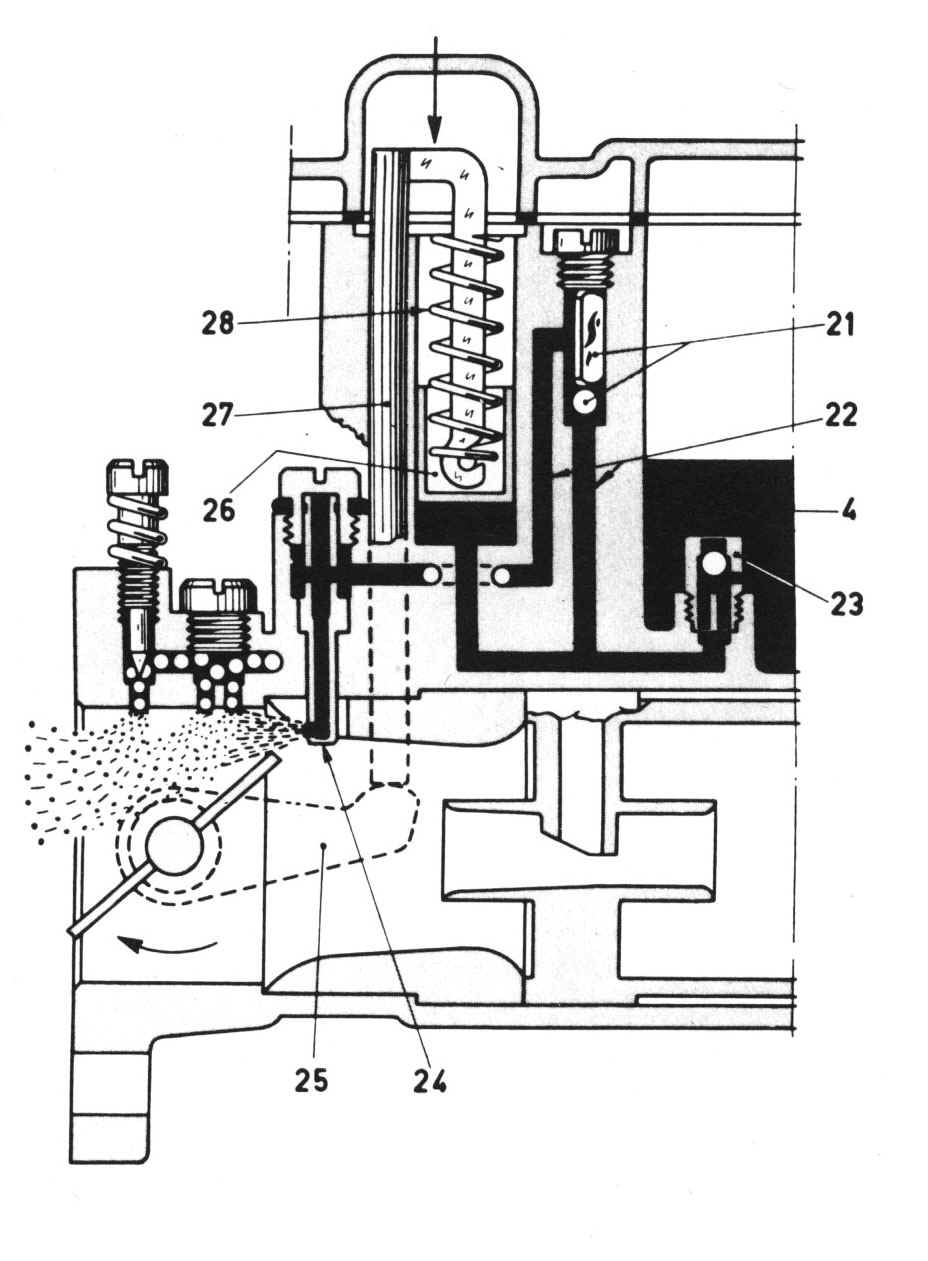

Most carbureted Lamborghini V12s use a two-barrel, side-draft Weber, the legendary DCOE. My 1985 Countach 5000s has 6 of the 45 DCOE versions of these marvels. The accompanying figure shows the accelerator pump circuit within this carburetor. When the throttle is opened, a control rod is moved which allows a spring-loaded piston to act upon a small, fuel-filled chamber. The piston pumps fuel from this chamber into two separate locations: through the auxiliary jet (which feeds the engine) and through a check valve back into the main float bowl (which doesn't directly feed the engine).

The split-flow of this circuit is the source of the throttle hesitation problem. The two-way split of fuel from the pump allows very careful tuning of the quantity of fuel which is injected into the engine. A precise hole in the check valve (labeled #23 in the figure) bleeds excess fuel from the pump back into the float bowl. The size of this hole is critical: the larger the hole, the more fuel is bleed back into the float bowl, and the less fuel is injected into the engine. For some reason, cars delivered from Lamborghini specified a rather large hole for this check valve. As a result, when the accelerator pump operates on the Lamborghini, most of the fuel is simply reinjected back into the float bowl and very little is injected into the engine; hence, the stalling and hesitation problem on carbureted cars.

The solution for this problem is simple: reduce the size of this bypass hole, or close it completely. I should interject a personal note at this point: there's lots of things to adjust on the accelerator pump circuit, and I haven't optimized any of them. The "quick and dirty" solution I first tried showed such a dramatic improvement, that I didn't bother with any further tuning. This quick and dirty solution is as simple as it gets: solder shut the bypass hole on the check valve. I don't proclaim that this is optimum tuning for this circuit, and it certainly doesn't help the fuel consumption. But it brought a dramatic improvement in throttle response from my Countach, and several other Lamborghini V12s showed similar improvements including an Espada and another Countach 5000s.

Another disclaimer: any use of third-person or other descriptions in the following does not imply or endorse the use of this information by anyone. Use this information at your own risk. The author disclaims all liability associated with use of this information.

Here's how I closed the bypass hole on the check valve:

I performed this procedure only on a stone-cold engine. I disconnected the battery so I wouldn't risk any sparks or other ignition sources. I'm working on parts containing raw fuel, so I'm very careful. My fire extinguisher is close-by in my well-ventilated garage.

- Remove the "mickey mouse" hat from the top of the carburetor.

- CAREFULLY remove the fuel connection (banjo-type fitting), and be prepared to catch any excess fuel which runs out.

- Remove the five bolts which secure the top of the carburetor.

- CAREFULLY lift the top of the carburetor off the main body. The float and other hardware will dangle below the top plate, and you don't want to bend or alter any of these settings.

- The accelerator pump check valve is located in the bottom of the carburetor bowl (underneath the fuel). It has a flat-bladed screwdriver slot, and can be found in the center of the bowl, in the narrow part between the two reservoirs. There is only one check valve in each carburetor. Feel around in the bowl with your fingers, and you'll locate the valve.

- Unscrew this valve with a flat-bladed screwdriver. Notice the small ball in the middle (the check valve) and the hole in the side. My Countach 5000s had a valve stamped "70" meaning the hole was calibrated to flow fuel equivalent to a 0.70 mm perfect hole. This is the bypass hole I wanted to close off.

- Solder this hole shut. I did this by first applying a liberal amount of solder flux to the hole, and then heating the valve with a soldering iron. Once the flux boils, quickly apply solder to the brass valve body. The solder should flow smoothly on the brass, and the hole will quickly fill. There's a hard, plastic ball in the middle of the valve, and if you hold the iron to the valve for too long, you could risk melting this ball. To be safe, I held the valve in a vice to help conduct heat from the end and to prevent melting the ball.

- I liberally sprayed WD40 through the valve to remove any excess flux. Shake the valve to ensure the ball is still moving freely.

- Installation of the check-valve back into the carburetor is trickier than removal. The problem is getting the valve rethreaded. Here's a hint: use a 6" piece of rubber tubing slipped over the valve as a thread starter. Once you get the valve rethreaded, pull the tubing off and hand-tighten the remainder with a screwdriver.

- Reinstall the top of the carburetor and the fuel line. It's best to use new gaskets so nothing will leak. CAREFULLY check all retightened fittings to ensure against fuel leaks. I ran the fuel pump for a few minutes and observed all the gaskets and connections until I was convinced nothing was leaking.

- You're done!

Replacement check valves are available from Pierce Manifold (address and phone number at the end of this article), as are check valves with various calibrated holes. If I ever get the time, I'd be tempted to try several sizes to optimize both the throttle response and the fuel economy. The previous procedure is easily reversible by re-drilling through the solder with a set of calibrated carburetor reams. One time-consuming experiment would involve re-reaming the holes to progressively larger sizes, and noting the response and fuel consumption after each increase. Such information would be extremely useful to the owner of any carbureted Lamborghini.

So, that's it! I found my throttle response dramatically improved. Instead of the dull lag when you hit the throttle, I now get a deep throaty roar and an immediate pull.

Weber parts:

Pierce Manifolds, 8910 Murrary Ave, Gilroy, CA 95020, (408) 842-6667

Accelerator pump check valves for the Weber DCOE have basic part number 79701. Specify the size of the bypass hole as 000 (closed), or 0.35 to 0.90 in 0.05 mm increments.

Recommended Reading:

"Weber Carburetors", Pat Braden, HP Books #774, ISBN 0-89586-377-4, Los Angeles (1988)

[ Home ] [ Up ] [ Back ] [ Next ]